Andy Poole, legal sector partner at Law Society endorsed accountants Armstrong Watson, outlines the key factors to take into account when deciding what business structure to use for your law firm. (Updated 8 August 2024)

Andy Poole, legal sector partner at Law Society endorsed accountants Armstrong Watson, outlines the key factors to take into account when deciding what business structure to use for your law firm. (Updated 8 August 2024)

While law firms have traditionally been structured as partnerships (or sole practitioners), other options have become increasingly prevalent. A limited liability partnership (LLP) offers many of the benefits of a traditional partnership but with a greater degree of personal protection for the partners. More recently, new entrants have tended towards limited companies.

The structure you choose can have wide-ranging implications, from how you operate to how much tax you pay. There's no single right answer that works for all firms. You need to look at what matters to you and choose the option that best suits your particular circumstances.

"A business structure based purely on tax optimisation can lead to unintended consequences and misaligned objectives, hampering the firm’s success and profitability. Why allow the tail (tax factors) to wag the dog (business structure)?"

Glyn Morris, partner, Higgs & Son

Limiting your liability

At the risk of starting on a negative note, there's a clear distinction between structures that limit your liability – limited companies and LLPs – and being a sole practitioner or in a traditional partnership. Without limited liability, your personal assets are at much greater risk if things go wrong.

At the same time, you should recognise that even companies and LLPs aren't bullet-proof. If the firm becomes insolvent, a director of a limited company could face a claim of wrongful trading. Equally, members of an insolvent LLP can face a clawback of any payments received during the previous two years.

You will also put your personal assets at risk if you give any personal guarantees – for example, in order to raise finance for the firm. You may find that financing the firm, or taking on other substantial commitments such as a lease for your premises, is almost impossible without guarantees.

If you are required to provide any personal guarantees, you should aim to limit their scope. It may be possible to agree a cap on the total amount of the personal guarantee, or to tie the guarantee to an individual loan rather than the firm's total bank borrowings. In the excitement of setting up a new firm, it can be all too easy to accept potential liabilities that you may later regret.

Administration and disclosure

As far as setting up a new firm is concerned, the structure you choose makes little difference. For a sole proprietorship or traditional partnership, you need to notify HMRC. For a limited company or LLP, you also need to register the details with Companies House.

A more significant burden is the application process for the Solicitors Regulation Authority. This requires a great deal of form-filling and is likely to take at least a month. The process is more onerous if your firm is applying to be licensed as an alternative business structure, where non-lawyers will be involved in managing or owning the firm.

Administering a limited company or LLP requires continued filings with Companies House, generally on an annual basis or when there is a material change (eg appointment of a new director). This includes filing of accounts, though for smaller firms these can be abridged or filleted so that only a very limited amount of profit and loss information is publicly disclosed.

"If you're setting up a small practice on your own, a sole proprietorship is often cheaper and simpler than forming a limited company, at least to begin with."

Andy Harris, partner, accountants Hazlewoods

Governance and culture

The structure you choose can both reflect and influence the firm's culture.

Many lawyers see the traditional partnership as a natural way to foster a collegial culture. But for every collegial partnership, there's another partnership which operates as a federation of semi-autonomous practice areas, each focused on maximising their own billable hours.

A partnership can give a voice to each of the partners, helping to bring the best out of everyone involved. Or it can equate to management by committee, where difficult decisions are deferred and the status quo prevails. Structuring the business as a limited company may encourage more dynamic governance or make it easier to involve professional managers as part of an alternative business structure.

In terms of strategy, partnerships tend to create a focus on short-term profits. A partnership is not the most suitable structure for encouraging external investment to finance a longer-term strategy. It is perhaps unsurprising that new entrants focused on high volume areas of law – and investing heavily in technology and marketing – tend to be limited companies.

"What role do you – and your partners – want to have in managing the firm? Do you want a veto on key decisions, or would you rather just focus on practising law?"

Jon Davies, vice president (international), Travelers

Agreements among business partners

Clear agreements among the principals are vital. For a partnership, the key document is the partnership agreement (or LLP members' agreement). In a limited company, both a shareholders' agreement and the articles of association will have an impact.

Drawing up an agreement is an opportunity to do more than sort out practical details like profit-sharing and holiday entitlements. Even if you and your partners work together brilliantly, differences will inevitably emerge as personal priorities and circumstances change. Key issues to resolve include:

- Business strategy and personal priorities. For example, if one partner wants to maximise current income while another wants to invest for the future.

- What role in decision-making each individual will have, how decisions will be made and how disagreements will be resolved.

- What will happen if one practice area starts to contribute a disproportionate share of the firm's profits?

- Under what circumstances will it be possible to terminate an underperformer? In a limited company, what will happen to shares owned by an employee or director who is terminated?

- Any limits on the timing or number of partnership exits – for example, if several partners are likely to want to retire at around the same time.

- Clear valuation mechanisms for shares on entry and exit, including who would acquire shares and under what circumstances.

Flexibility for the future

The more flexibility you can build in, the greater your firm's ability to cope with future changes. In particular, you should look ahead to changes in the firm's principals – the partners, members (of an LLP) or directors and shareholders (in a limited company).

With a suitable agreement in place, a partnership or LLP can be a very flexible way of dealing with changes to the partnership or individual profit shares.

Structuring the profit share may be more challenging in a limited company and is certainly less flexible. Any change to the firm's ownership can also be more complex, necessitating a share valuation on the issue, transfer or cancellation of shares with the associated tax considerations and potential liabilities.

That said, a limited company does offer scope for individuals to be flexibly involved – as employees / directors / shareholders. This can be a good structure for a firm where ownership is less directly tied to legal talent – for example, if the firm has significant outside investment or involves professionals from other disciplines as well.

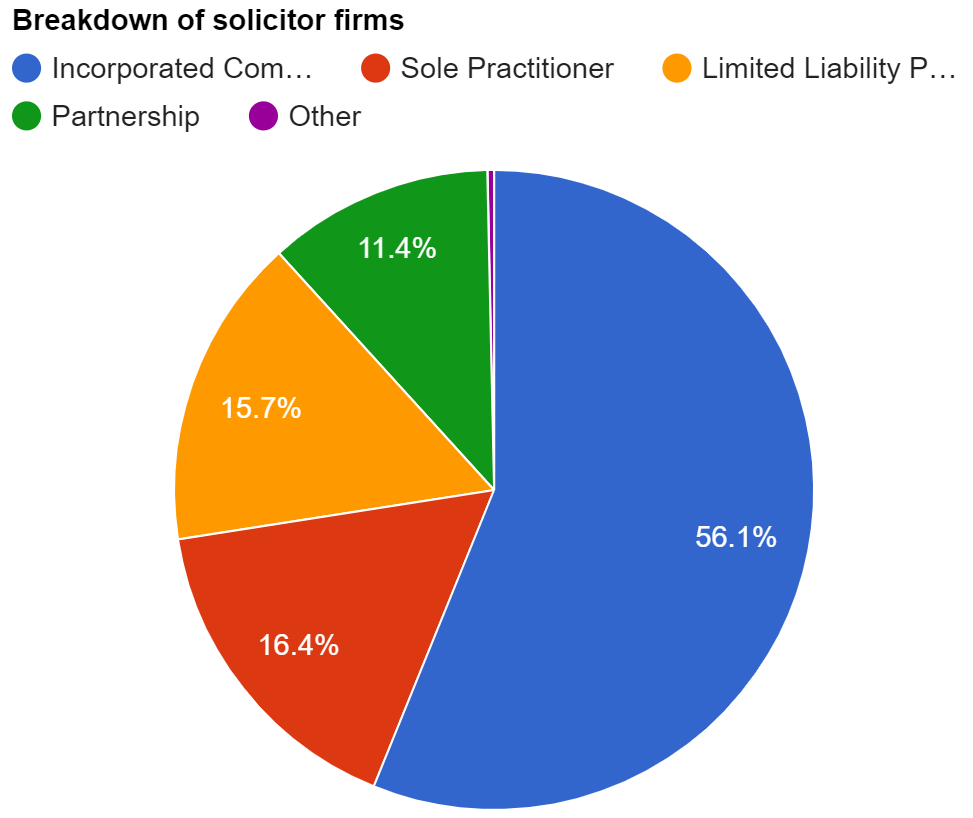

10 years ago, 27% of law firms were limited companies and 27% were partnerships. Today the figures are 54% and 12.5% respectively.

Breakdown of solicitor firms July 2024, Solicitors Regulation Authority

Succession issues

Plan ahead for how the firm can attract new lawyers – either at junior or ‘partner' level – and how existing partners will eventually be able to retire or otherwise exit the firm. It can be difficult to strike the right balance between two potentially opposing viewpoints.

A system that allows partners to build up (and eventually realise) the value of their equity in the firm encourages long-term thinking and investment. But it can be difficult to attract new partners or junior lawyers if they will be required to make a substantial contribution to buy in to the firm.

Equally, a firm where profit is shared exclusively among full equity partners – as may be the case in a traditional partnership – may be less attractive to junior lawyers than a structure which allows a more gradual progression through the ranks.

Tax

Partnerships and LLPs have a similar tax treatment, with partners taxed as self-employed at the standard rates of income tax (ranging between 20% and 45% depending on level of earnings). Tax is paid on each individual's share of the profits, regardless of whether these are drawn or reinvested in the firm.

In a limited company, profits are taxed at lower corporation tax rates – 19% for profits less than £50,000, 26.5% for profits between £50,000 and £250,000, and 25% on all profits above £250,000 (subject to any other companies that may be under common control). Any salaries paid (to yourself and other employees) are subject to income tax and National Insurance contributions. The taxation of dividends varies, with an initial tax-free allowance for the first £500 followed by increasing rates (from 8.75% to 39.35%) depending on which income tax band you are in. Where profits are retained within a corporate structure it is necessary to consider when and how those profits will ultimately be extracted and the tax position that is likely to apply then.

Any gains you make from selling your interest in the firm are likely to be subject to capital gains tax. Again, this is at substantially lower rates than income tax – as low as 10% if you qualify for entrepreneurs' relief (now known as Business Asset Disposal Relief).

What all this means is that, in very broad terms, a company is likely to be the more tax-efficient structure if you will be retaining substantial profits in the business. If you plan to draw the bulk of your profits, the difference depends on the exact amounts involved and has become even more fact-specific given recent increases in tax rates.

Your best approach may be to talk through your expectations with an accountant who can model how different structures might affect your total tax payments. Bear in mind that tax regulations can and do change over time, so there will always be a degree of uncertainty over what is the best option.

"Tax planning works best when you look at the whole picture – from setting up the firm to retirement (and ultimately inheritance tax). For example, a firm changing from a partnership to a limited company needs to consider SDLT on any property transfer and CGT on any chargeable assets."

Jason Mitchell, partner, accountants PKF Francis Clark

Law firm structure top ten

- There is no one right answer – look at all your plans for the firm before making a decision.

- Don't let tax be the key factor you take into account.

- Be clear about your tolerance for risk – and whether you need the protection offered by an LLP or limited company.

- Decide whether the (relatively limited) disclosure requirements of a company or LLP are acceptable to you.

- Understand how firm structure might impact on business strategy.

- Think about the culture you want to promote and what the governance arrangements should be.

- Take into account the need to balance partners' interests with those of junior lawyers and potential future recruits.

- Look ahead to anticipate likely changes – including your eventual retirement.

- Take advice on the likely tax impact of different structures and steps you can take to minimise tax.

- Thoroughly discuss your plans and priorities with your partners and draw up suitable agreements.

Why do law firms choose Armstrong Watson?

It’s because this accountancy firm has built an outstanding reputation in the legal sector, working as preferred partner of the Law Society.

See also: